Discovery

Discovery for Product Managers in Government

Note

This post is a work in progress published on GitHub where you can leave comments and suggestions.

Discovery is hard.

There’s recently been chatter about the discovery phase within the government digital community here in the UK, acknowledging that it can be hard to do well and that we can improve. This is something that’s emerged here at the Ministry of Justice (where I’m lead product manager) and across government during the development of a cross-government product management community of practice). Will Myddleton just published a post covering a lot of the stuff that makes discovery hard.

I’ve been chatting with Helen Mott (Head of Delivery at the Ministry of Justice) about discovery and Helen’s been working on explaining it from a delivery perspective. I thought it’d be useful to do the same from a product management perspective.

I’m a product manager, wtf is discovery?

Discovery is the initial design phase for public services in which you check if there’s a problem, if it’s worth solving and if you’re the best people to solve it.

I’ll repeat that because it’s my main point. I think that I should ask three questions during discovery and then work with my team to answer them with enough certainty to kill or continue the product:

- is there a problem?

- is it worth solving?

- has it been solved already?

You’re unlikely to answer these questions in order and are likely to jump around all three, with insights in one of them changing the others.

Is there a problem?

Make sure your users want your service before you build it.

You should be talking about problems when you start a discovery phase. You should not be talking about solutions.

Your job as a product manager is to avoid committing resources (money, people, time) to a solution until you believe there is sufficient certainty that the solution is valuable. This approach is based on decades of product insights and was pulled together in The Lean Startup. The Lean Startup brings a management approach to areas of extreme uncertainty (like developing a service) focussed on validated learning, rapid build-measure-learn feedback loops, and measurement and accountability. It’s about taking a scientific approach to decision making. So you start by defining the problem that you want to solve.

You need to find out if there are people who will truly see the value of your product. This means that it’s not enough to simply spot a problem (e.g. ‘the current paper form takes ages and goes missing loads’), you need to dig deeper. Jock Busuttil was previously lead for the MOJ’s product community and has written a product management book called The Practitioner’s Guide to Product Management that identifies a key set of questions to be answered about the problem you want to solve:

- Is it pervasive? Who specifically has the problem and does it affect lots of people?

- Is it urgent? Do those people need the problem to be solved right away or can they wait?

- Is it complex? Are people able to solve the problem for themselves or do they need someone else to solve it for them?

- Is it valuable for users? How painful is the problem for them and would they be willing to change their behaviour and use a new or different solution?

- Is it valuable for your organisation? Will solving the problem save more money than it costs to build the solution?

You are likely to reframe your problem during this process and may even change your primary user. This is important and valuable as you the scope of your problem to be feasible to solve. You’ll often find that you start with a massive problem space and refine this to something with a narrower focus but greater feasibility of being solved. The Institute of Design at Stanford’s design thinking process has been knocking around for longer than The Lean Startup and refers to this as a define mode in which you “unpack and synthesize your empathy findings into compelling needs and insights, and scope a specific and meaningful challenge. It is a mode of ‘focus’ rather than ‘flaring’.” This is important: the two goals of the define mode are to develop a deep understanding of your users and the design space and, based on that understanding, to come up with an actionable problem statement

Suggested reading:

- Manifesto for Agile Software Development and principles behind the agile manifesto

- The Lean Startup

- The Practitioner’s Guide to Product Management

- Design Thinking Bootcamp

Is it worth solving?

Looking at Jock’s questions about the problem you want to solve, you’ll notice that a couple of them refer to a solution. This doesn’t mean that you’re expected to build or even choose a solution at this stage but it does mean that you should have done the minimal exploration of potential solutions needed to make a decision about whether or not to spend money on a solution in later stages (i.e. should you proceed to Alpha). You’re looking to find what Steve Blank calls problem/solution fit. In short, do you have a problem worth solving?

You should work with your team and use validation techniques in order to make scientific decisions. List your assumptions and prioritise them in order of risk then run experiments to test these assumptions, framing each assumption as a hypothesis and providing clear pass/fail criteria for the test. In this way you will you will refine your problem and potential solution.

In practice, you might want to work on a physical board or a Trello board and:

- have a huge braindump of assumptions

- label them as user assumptions, problem assumptions or solution assumptions

- decide on your core assumptions

- prioritise your riskiest assumptions

- design an experiment to test the assumption

- agree the pass/fail criteria for the experiment

- run the experiment and use the outcome to inform your decision making process Repeat this until you have refined you have enough data to make a decision as to whether you should kill or continue with the product.

I was asked to give an example of an assumption. Until recently I was Product Manager for the MOJ’s Cloud Platform, the hosting, deployment and testing service for developers. We had assumed that devlopers needed bespoke settings and concierge services but our user research showed that there is limited variety in MOJ software and developers wanted a simple setup process. This meant that we were able to change our approach, focussing on standardisation, sensible defaults and self-service for developers (which allowed us to save over 70% of hosting costs, amongst other things).

You can explore solutions at this stage without committing to building one. The Lean Startup defines a minimum viable product as the minimum needed for a build-test-learn feedback loop. This doesn’t have to be code, it can be things like paper wireframes, digital wireframes or using an existing solution as a proxy. You shouldn’t commit to a solution at this stage but you should run experiments to test if your problem is feasible to solve.

Suggested reading

Has it been solved already?

Let’s assume that you’ve found a problem that is valuable and feasible to solve. You should carry out market research to find out if someone has solved it already. If you think that your problem is likely to be solved by a case management system and you find an existing commercial option that seems to fulfil your users’ needs at a low price then you might want your Alpha to focus on testing this (rather than building your own).

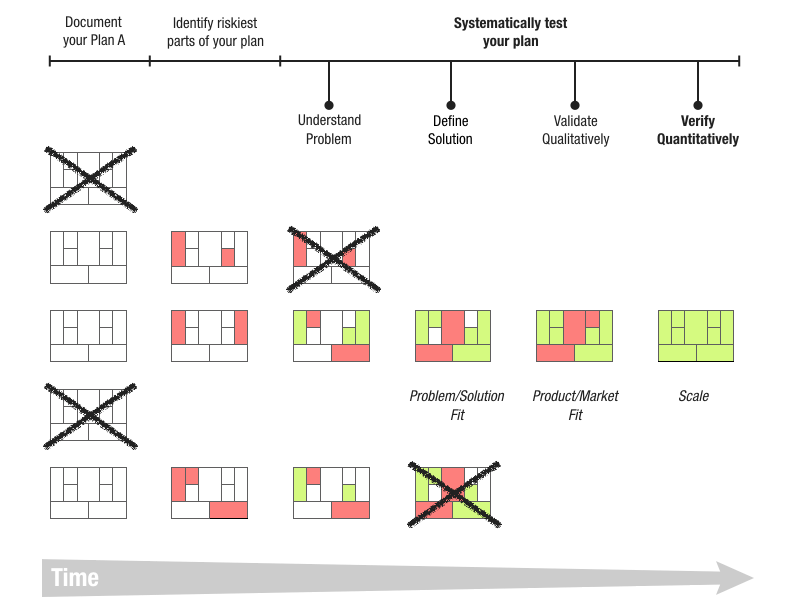

A lean canvas is an excellent way to bring all of your insights together and ultimately decide if you should go ahead an try developing a solution to the problem you’ve identified. In his blog post It’s Time to Fire the Business Plan for Good, Ash Maurya uses a helpful visual representation of how your lean canvas is likely to develop during discovery, as you learn more about the users, their problems, and the possible solutions.

A lean canvas is a modification of a business model canvas, something I’ve previously blogged about.

For me, the key section of the lean canvas is the ‘unfair advantage’ section. You should only continue with a product if you have an ‘unfair advantage’ when it comes to developing a solution. In government this means that we shouldn’t always assume that building in-house is best. If someone elsewhere in government or a commercial organisation already has a solution then we should consider using that instead. As a product manager, we should ensure that we don’t recreate the wheel.

The bottom line

It all comes down to the bottom line. Literally. Adapting the lean canvas for government, the goal of discovery is to uncover COSTS (cost of the problem; cost of the solution) and VALUE (what is it worth to solve the problem?). As a product manager, your job at the end of discovery is to have established whether or not the value outweighs the costs, and to give the degree of certainty you have in your decision.

Top discovery fails

Here’s my personal list of top discovery fails:

- falling in love with your solution

- no clear return on investment

- no clear path to users

- flaring instead of focussing

- a weak unique value proposition

- no unfair advantage story

- problem isn’t specific enough

- lack of metrics of success.

General Discovery articles

- 8 things I learned about data discoveries, Kieron Kirkland - GDS

- Discovery from Day One, Dan Mutton - ThoughtWorks

ENDNOTES

Here are a few things that I’ve not yet managed to incorporate in this post:

You can stop something after Discovery; equally, a single discovery could lead to mulitple things; be good to have examples of both

Alpha and service assessment: what’s the handover to alpha? how to engage with continuous service review at discovery?

Can I use real life examples to bring this to life or would it make the post too long?

Team: who are the right people for discovery? The product manager poses the questions in this post but answering them is a team sport.

Portfolio management: this post pre-supposes that discovery teams receive problem statements. What do you do when your a discovery you’re handed already pre-supposes a solution?

Account management: do our ‘clients’ understand the discovery phase when they commission work of government digital teams?

I haven’t mentioned vision, and have limited strategic tools to the business model canvas/lean canvas. How does the roadmap fit at this stage? This post is a useful one to pick up on this point: http://www.slideshare.net/sachmonkey/the-art-of-product-management-58156816

- https://www.thoughtworks.com/insights/blog/discovery-day-one

- https://twitter.com/CarlaDownes/status/821813084092301313