Who's got time for digital transformation?

This is the fourth in a short series of posts about digital transformation’s need for business models, you can read the introductory post here.

Agile approaches added a time dimension where previously there was none […] The Waterfall model was based on taking a point-in-time snapshot of the information we know and using it to create a long-term plan that we would adhere to. The Agile insight was that we should change our notion of what features will create business value over time as more information becomes available […] Agile approaches added a time dimension where previously there was none.” The Art of Business Value, Mark Schwartz

The value of our work changes over time. We can start to understand this by defining at least two stages in the lifecycle of our products: (i) exploring new opportunities, and (ii) exploiting existing opportunities. Understanding that our product and their value changes over time helps us to refine the common assumption that ‘delivery is the strategy’.

‘Delivery is the strategy’ was the rallying call of digital transformation in government for the longest time. The truth is that ‘delivery is the strategy’ is a tactic. It’s something used at the beginning of digital transformation to build an organisation’s emotional confidence in a new way of working. This rallying call is often interpretted as ‘the delivery of stuff is the strategy’, because ‘stuff’ gives everyone confidence that things are happening. It’s a period of rapid investment in new opportunities. And it’s critical for the first 1-2 years of digital transformation, generating opportunities for the digital pipeline and demonstrating to colleagues that digital teams can be trusted with work. However, we quickly build up a lot of stuff that needs to demonstrate return on investment and be supported and maintained and have to figure out models for ongoing funding and continual improvement. It’s not uncommon to suddenly find too much work in progress and less return on investment than planned, with issues quickly arising.

There’s an increasing move to the notion that the era of move fast and break things is over, with the realisation that things can go worong when delivery remains the whole strategy beyond the the first 1-2 years of digital transformation. We are just realising that we need to go broader and deeper than ‘brand-new’ and ‘public-facing’, into the realm of ‘legacy’ and ‘staff-facing’. And even further than that: into the underlying business models by which we operate.

Does delivery remain the strategy, or is the era of move fast and break things over? The truth is that both things are required and need to coexist. The truth is that the era of lurching from one extreme to another is over. We absolutely need time and space to generate new opportunities in under conditions where we can move fast and break things. And we absolutely need space where existing opportunities are cared for and optimised under more stable and risk-averse conditions. We need to stop the all or nothing mentality that drives us to lurch from one extreme to the other. We need mutliple sets of conditions that co-exist, and to start using them strategically, where and when they are most useful.

Explore or exploit?

If we look at the lifecycle of a product, we can start by breaking it into two stages that help to balance new opportunities with existing opportunities. These stages are called ‘explore’ and ‘exploit’. Take a look at the table below for a summary of these stages, based on the summary in The Lean Enterprise.

| — | Explore | Exploit |

|---|---|---|

| Strategy | Radical or disruptive innovation, new business model innovation | Incremental innovation, optimising existing business model |

| Structure | Small cross-functional multiskilled team | Multiple teams aligned using principle of mission |

| Culture | High tolerance for experimentation, risk taking, acceptance of failure, focus on learning | Incremental improvement optimisation, focus on quality and customer satisfaction |

| Risk management | Biggest risk is failure to hit product/market fit | A more complex set of trade-offs specific to each product/service |

| Goals | Creating new opportunities, discovering new opportunities within existing portfolio | Maximising yield from existing opportunities |

| Measure of progress | Achieving product/market fit | Outperforming forecasts, achieving planned milestones and targets |

‘Exploit’ is the default of the Civil Service: a risk averse approach to incrementally improving existing opportunities. This approach does not work well for developing new opportunities. The Government Digital Service introduced the conditions for ‘exploration’ - this is what the service manual and phases of an agile project provide: a means of developing new opportunities. But this approach does not work well for ‘live’ opportunities. We need both exploration, and exploitation.

Product/market fit

You’ll notice that there is a tipping-point from explore to exploit, referred to as product/market fit. This concept is most commonly used in a commercial value context, where it kind of means the point at which we’re confident that a product is actually working in the marketplace, and we have the confidence to invest in growth of the product. However, we’ve previously established that we can measure value without profit, and that commercial concepts normally apply in public services with just a few tweaks. In the context of public services, we could take product/market fit to mean the mean adoption of our software by users in order to justify the cost of development. In this situation we would say that:

- X number of people need to use our software in order to justify investment we’ve received

- ‘use’ is defined as completing the user journeys required for the software to be valuable

- our one metric that matters during exploration is the % of our target adoption that we’ve reached

- secondary metrics would be how long we’ve taken to reach product/market fit, and what % of our available investment we’ve spent to get there.

Notice that I use the word investment. We should revist our use of the word ‘budget’. We should seek investment based on the potential value of solving problems, over seeking budgets based on the cost of building software.

Three horizons

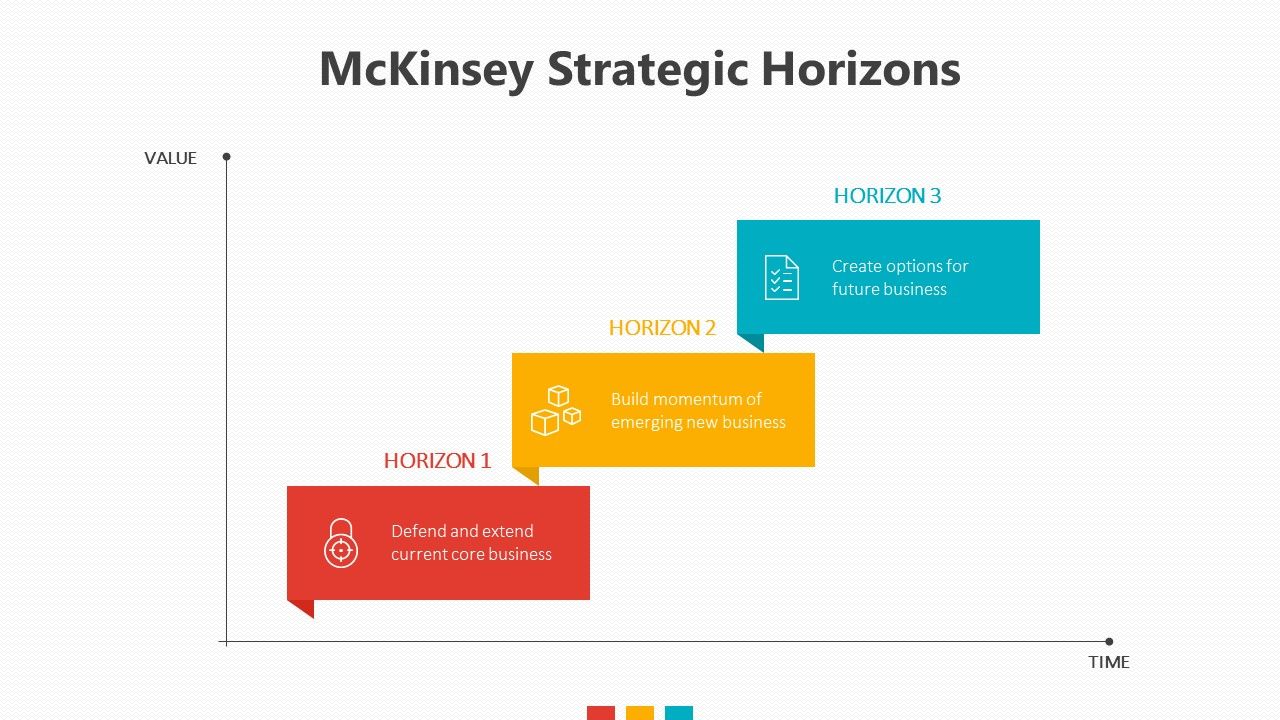

We can use the concept of having different conditions based on ‘time’ and use it to inform investments at a portfolio level. If we only invest in the shiny and new then we never reach the point of return on investment. If we only work on our existing stuff then we reach a point of intertia. We need to optimise the value of our current opportunities whilst still developing new opportunities. McKinsey’s three horizons of growth is an enduring model that gives us a way of thinking about this. In the below model, the ‘exploit’ phase is expressed as ‘horizon 1’. Horizon 1 represents the core business of our organisation, well-established and successful opportunities that generate our main return on investment. The ‘explore’ phase is broken into two horizons, ‘horizon 2’ and ‘horizon 3’. Horizon 2 represents emerging opportunities that are likely to be successful but which require significant investment. Horizon three represents ideas that might become opportunities down the road but are currently in the research phase.

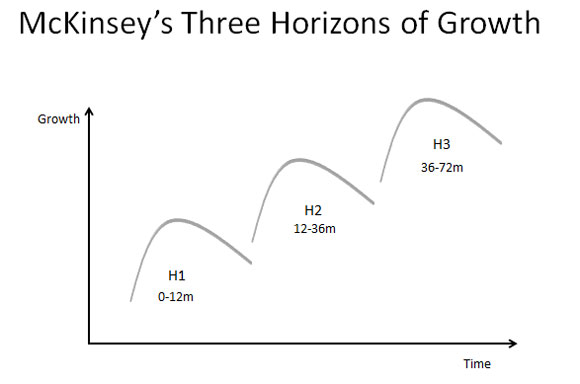

These horizons can be used to help manage risk and increase the likelihood of return on investment/benefits realisation. The diagram below suggests a common use of this model to help balance a portfolio:

- Horizon 1 (established opportunities) contains our best investment opportunities. Research has been carried out, large investment has been made, and we’re already seeing return on investment/benefits realistion. Investing in this space is likely to see return on investment within 0-12 months (so potentially within the same financial year as the investment is made)

- Horizon 2 (emergent opportunities) contains future opportunities but that require significant levels of investment. Investing in this space remains pretty high-risk but is crucial if we’re to continue to grow as an organisation. Investing in this space is likely to see return on investment within 12-36 months.

- Horizons 3 (ideas in the reseach phase) contains our riskiest investments, and our best chances to be transformational. Investing in this space is likely to see return on investment within 36-72 months.

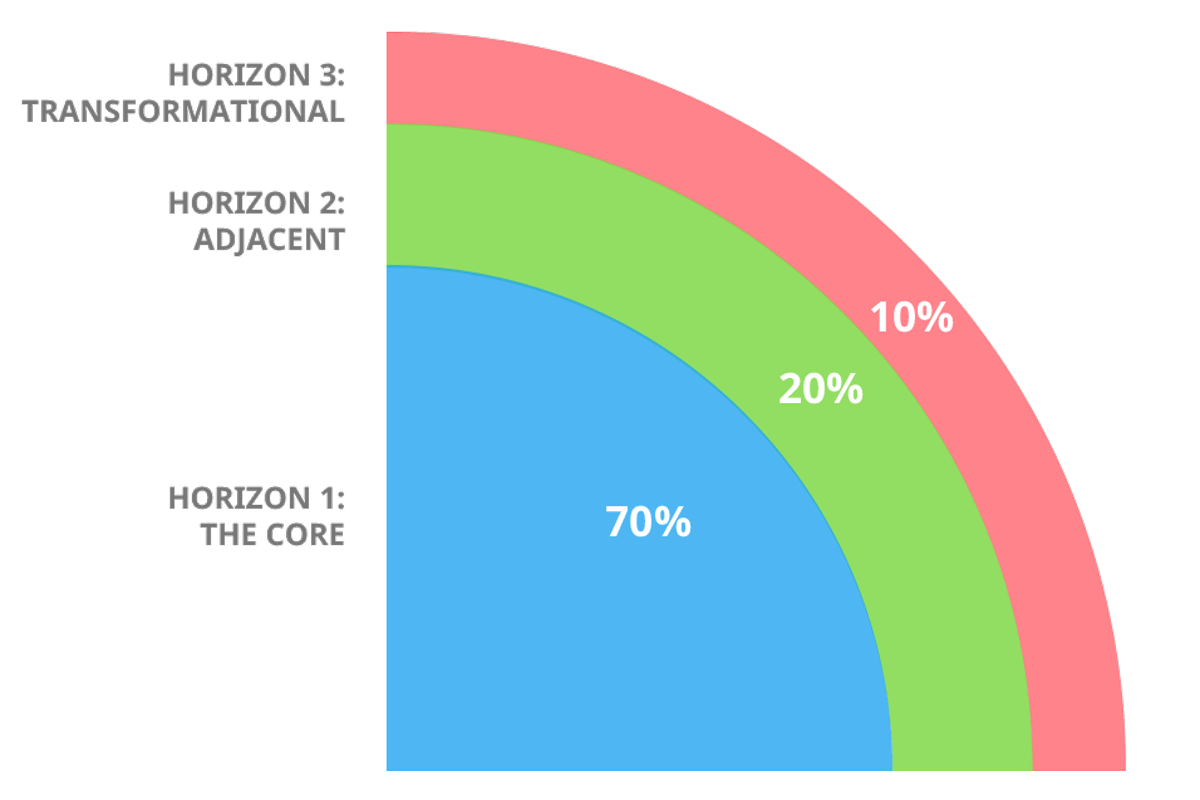

We need all three horizons in our portfolio in order to optimise the value of our current opportunities whilst still developing new opportunities but we should not invest equally in each horizon. The below diagram shows a common spread of investment across the horizons in order to maximise return on ivestment whilst investing in the future:

- Horizon 1 (exploit): 70% of available resources

- Horizons 2 (emergent opportunities): 20% of available resources

- Horizon 3 (research): 10% of available resources

Balancing a ‘digital’ portfolio

Remember we said that the phases of an agile project effectively gave the Civil Service a way of exploring new opportunities? We can use this realisation to think of the phases of an agile project as relating to to horizons 2 and 3.

We can think of discovery* and alpha (and anything that proceeds them) as research into ideas that might emerge as opportunities. This is horizon 3. We should probably invest around 10% of our available resources in discovery, alpha, and anything that proceeds these phases.

We can think of beta and the beginning of live as emergent opportunities. This is horizon 2. We should probably invest around 20% of available resources in beta, and early live phases.

Remember product/market fit? Well that’s the point at which an opportunity tips from exploration into exploitation. Which is the same as tipping from horizon 2 to horizon 1, according to our thinking in this post. We have a slightly odd situation where there is no service assessment to check if we ever hit product/market fit, or ‘benefits realisation’. The final assessment takes place at the end of public beta. It’s called a ‘live’ assessment but only because it gives permission to become ‘live’, not because it’s actually assessing that we’ve hit product/market fit. If we were to have a ‘product/market fit’ assessment, then passing it would more us into the exploitation phase, or horizon 1. This is where our lowest-risk, quickest return on investment is likely to sit. We should probably invest around 70% of our resources in this space.

‘Digital’ is often pitched as cost-saving, and this is probably true in the long-term in the long term (36-72 months). But when ‘digital’ is the answer for in-year cost-savings, and digital is being used to develop new stuff that’s starting in horizon one then we’re unlikely to see return on investment as measured by cost-savings in the desired time frame.

- We have an ongoing debate within digital teams about whether discovery ever ends, or if it’s ongoing. Personally, I agree that research is ongoing throughout the product lifecycle. However I also agree with my colleague Nabeeha Ahmed, that not all research is ‘discovery’. I subscribe to Roman Pichler’s definition of product discovery as ‘finding out if and why a product should be developed’.

Prioritising activity within the ‘exploitation phase’ or ‘horizon 1’

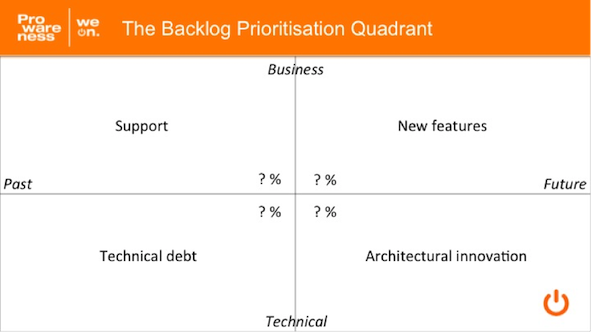

Let’s say that we’re investing 70% of our resources in our core business, in our strongest existing opportunities. How do we balance the need for new features against the need to pay-down technical debt, for example? We steal an old product management tool and apply it at a large scale. Let’s take Barry Overeem’s prioritsation quadrant.

Our portfolio requires four activities to happen concurrently within exploitation phase/horizon 1 if our software is to remain evergreen and not become what’s commonly known as ‘legacy system’:

- new features (responding to new insights or changing user needs)

- improved support (software is only valuable if it’s used; our support model makes sure it’s used)

- technical debt (maybe we originally hosted on privately and now we need to migrate to public cloud)

- technical innovation (the work down to realise that public cloud is now a ‘thing’ and to see if we can make use of it, for example).

All of these activities need to happen concurrently in order to avoid technical debt becoming so massive that it becomes so massive that it swamps everything else, swallowing all investment and focus and becoming the sole focus for our organsation (possibly in the form of a programme). However, we are unlikely to invest in all activities equally. And the balance of investment in each activity can (and probably should) vary from one period to the next. What’s important is that, for the live software in our portfolio, all activities are happening concurrently at all times.

Retirement

There’s a point at which we can no longer justify investment in software on our portfolio. Maybe people have stopped using it. Or a commercial, off the shelf product has emerged that’s much more cost effective. Or we’ve found duplicate software elsewhere in our portfolio and can conflate two pieces of software into one. In any event, return on investment has dropped too low to continue with investment.

How do we know this. Returning to the starting point of this whole series of posts, we should understand the business model for each piece of software and our portfolio as a whole, and regularly review them. When the costs outweigh value, we need to take action.

Importantly: retirement can happen at any time during the product lifecycle outlined in this post. I used to teach at General Assembly and would tell students to expect that 7 out of 10 ideas should either be retired or significantly change through research and development. Applying the same logic to our digital work in government, we should expect that for every 10 ideas that begin in discovery, 7 of them should them should either be retired or undergo significant change before leaving beta.